Japanese aesthetic sense and Kyoto aesthetic sense

Yoshie Doi

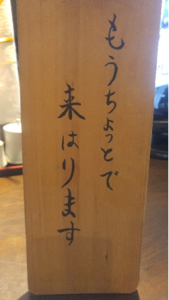

Reservation information sign for Yaosada. |

|

Photographed in spring 2024.

Located just down from Shijo Shinmachi, Gohandokoro Yaosada https://www.yaosada.com is a popular restaurant in a Kyoto townhouse. People line up before the restaurant even opens to enjoy delicious Japanese food. The reservation sign I saw at the restaurant was heartwarming. The reservation sign on the counter seat read, “They will be here in a little while.” “Reserved seats” is too impersonal, but this kind of sign is heartwarming.

This warmth and solace for both customers who have made a reservation and other customers who see their reservation ticket is the essence of Kyoto Rakuchu hospitality.

The other day, I told my daughter a story. “A father left a will saying, ‘Take this old watch to a watchmaker and ask how much it’s worth.'” The son told her that the watchmaker told him, “Because it’s an old watch, it’s worth 500 yen.” Then, she said, “Go to the museum and ask them for an estimate.” The museum appraised the watch at 100 million yen.

It is said that his father advised his son, “Put yourself in a place where you can understand your own value.” This is one example of how value can change depending on the ability to discern, but Japanese aesthetics are also different from those in the West.

There is an agency for Kintsugi workshops near my office. Kintsugi is a traditional Japanese repair method for chipped tea bowls and broken tableware. In the West, chipped tableware loses value, but in Japan, by repairing a chipped tea bowl with Kintsugi, its value increases. This is the Japanese sense of aesthetics. So they introduce you to craftsmen who can do Kintsugi.

The Oido tea bowl, which was broken by Hideyoshi’s servant and repaired with gold, has been passed down to the present day, beautifully restoring the five pieces of the tea bowl. In the West, broken teacups are considered worthless and thrown in the trash, but in Japan, they are repaired with gold to further increase their value. This is Rikyu’s aesthetic sense. It is a culture of enjoying the passage of time, called wabi-sabi.

The mountain gate of Joshoji Temple in Takagamine is covered with concrete, but after many years, the areas where people have passed by will wear away and the gravel underneath will become visible. In other words, this is the same technique as Akebono lacquer, where the gravel is laid down so that it will become visible over time, and then cement is applied on top of it. This is a truly profound Japanese aesthetic sense. It is similar to the idea of Rikyu, who spread gravel on the open ground.

I am very happy and proud that Rikyu’s philosophy, which elevated the artistic quality of ordinary everyday scenery, is still deeply rooted in our culture today.

The end of document

Translated by Masami Otani